Nearly half of health system dollars flow through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, giving the federal agency a dominant role in shaping how care is financed, delivered, and measured. While much of the agency’s work is administrative, it also leverages its powerful position to shape the future of care with “innovation models” that experiment with payment incentives and delivery systems to test what works before scaling it across the nation.

How innovation models are changing

Under the Biden administration, the CMS Innovation Center emphasized equity and inclusion and tested models that aimed to bring more providers into value-based care without imposing steep financial risk. Under the Trump administration, the center has shifted its focus toward cost containment and accountability, trimming underperforming models and advancing new ones that demand greater financial risk from providers and clearer evidence of savings for taxpayers.

In May, the division announced a new strategic direction aligned with HHS Secretary Robert Kennedy Jr.’s “Make America Health Again” agenda. The new mission statement emphasizes preventive care, patient empowerment, and fiscal responsibility—framing the Innovation Center’s work around keeping Americans healthier while protecting taxpayers from rising costs.

The agency also announced early terminations for four existing models:

Primary Care First, a voluntary alternative payment model that offered PCPs a monthly population-based payment and performance-based bonuses and penalties.

End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices, which aimed to increase home dialysis and kidney transplantation through payment incentives tied to modality choice and transplant rates.

Making Primary Care Primary, a multi-payer model designed to help primary care practices build capabilities for integrated, team-based, and value-oriented care across medical, behavioral, and social needs.

Maryland Total Cost of Care, a statewide model that held hospitals and health systems accountable for the overall cost and quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries through global budgets and total-cost benchmarks.

The administration framed the cancellations as part of a broader effort to protect taxpayer dollars and streamline CMS’s innovation portfolio, arguing that these legacy models had failed to demonstrate clear savings or scalable results.

To help our members keep track of the evolving landscape and understand the administration’s new direction, we’ve compiled profiles below of four new innovation models that are moving forward in 2025 or the near future:

Transforming Episode Accountability Model (TEAM)

What the model does:

TEAM is a mandatory bundled payment model that holds hospitals accountable for the total cost and quality of care surrounding selected inpatient surgical procedures—such as lower joint replacement, spinal fusion, and coronary artery bypass grafts.

Each episode includes the hospital stay and 30 days of post-discharge care, with financial incentives or penalties based on spending performance and quality outcomes. The model aims to push hospitals, surgeons, and post-acute providers to coordinate more closely and eliminate unnecessary variation in episode costs.

Participation will be mandatory for hospitals in selected regions covering about 25% of the country.

Implementation timeline:

CMS announced TEAM in 2024, with the first performance year beginning January 1, 2026. The model is expected to run for five years, through 2030, with annual reconciliation and quality reporting cycles.

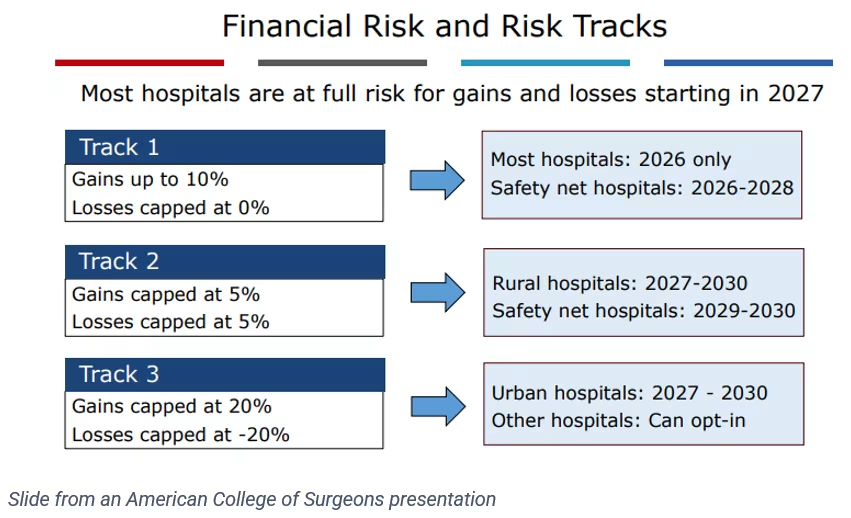

Each year, hospitals are assigned to one of three tracks with different levels of upside and downside risk, depending on their status as urban, rural, or safety net hospitals:

So What?

TEAM represents the next generation of bundled payments: broader in scope, stricter in accountability, and more focused on measurable savings. By targeting inpatient surgeries, the model threatens one of the most lucrative and margin-generating revenue streams for health systems.

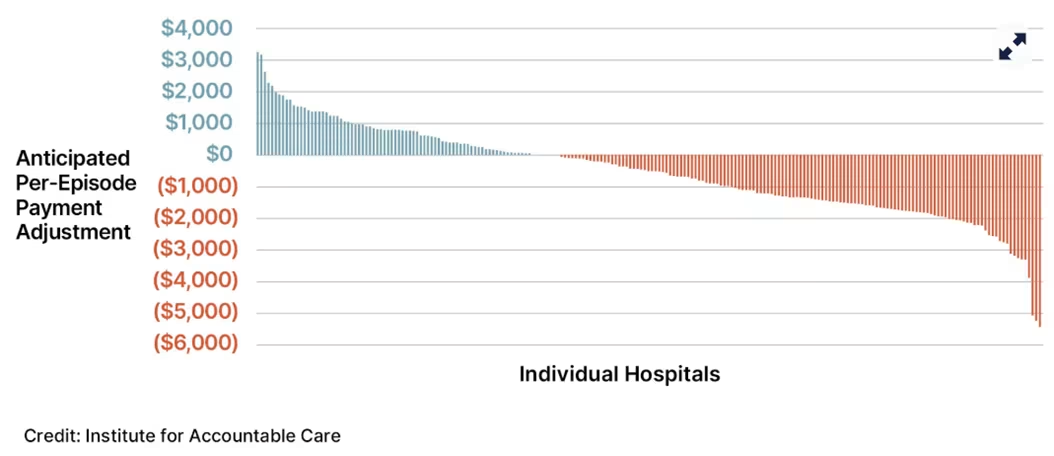

Hospitals with strong episode management, post-acute partnerships, and analytics infrastructure could see a financial boost. For many hospitals, however, the model could be a money-loser: analyses performed by Brandeis University and the Institute for Accountable Care anticipate that up to two-thirds of participating hospitals will lose revenue on net under TEAM:

The model also underscores CMS’s shift from voluntary to mandatory value-based arrangements, signaling that episode-level cost control and care coordination are becoming core expectations.

TEAM is a conceptual successor to the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BCPI) initiative, which featured a similar logic with episode-level accountability, quality-linked payment adjustments, and post-acute coordination. Unlike TEAM however, BCPI was voluntary—and providers that opted into that framework are now arguably more prepared to take on the new mandatory TEAM model.

Ambulatory Specialty Model (ASM)

What the model does:

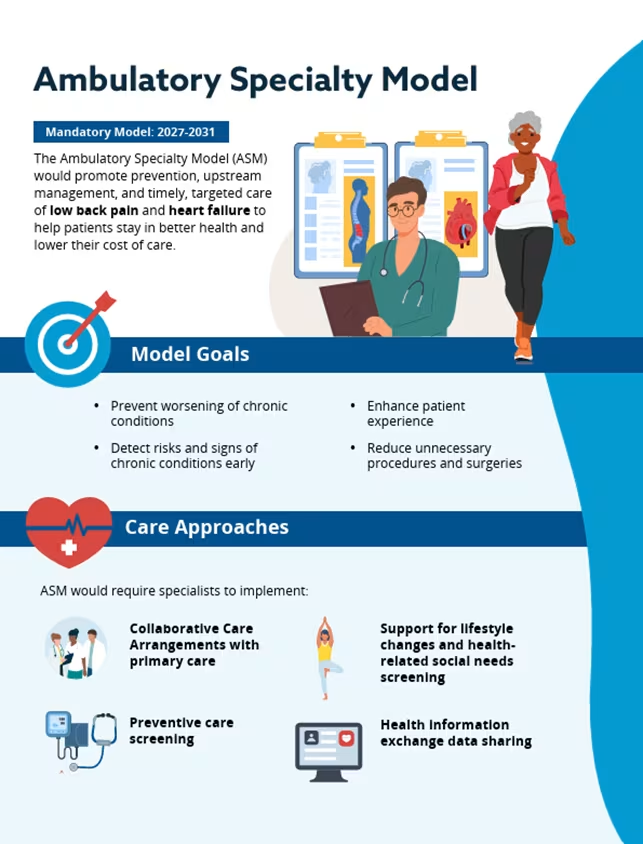

The ASM is a mandatory payment model that would hold outpatient specialists—starting with those treating heart failure and low back pain—accountable for both the cost and quality of care over defined episodes. It introduces two-sided financial risk, meaning clinicians can earn bonuses or face penalties based on performance across quality, cost, and interoperability measures.

CMS outlined six core goals for the model:

Improve collaboration between specialists and primary care

Use risk assessment to manage chronic disease and prevent additional disease

Reduce avoidable hospitalizations and unnecessary procedures

Increase transparency by comparing performance among participants and peers

Focus outcome measures on what matters most to patients

Align performance metrics with factors that specialists influence

Unlike MIPS, ASM bonus payments are based on relative performance compared to peers, rather than an objective benchmark set beforehand.

The model will be mandatory for applicable specialists in randomly selected regions that CMS plans to announce by the end of the year, representing roughly 25% of the country.

Implementation timeline:

The model was proposed in mid-2025 as part of the CY 2026 Physician Fee Schedule, with the first performance year expected to begin in 2027 after rulemaking and participant selection in 2026. The model is currently slated to be tested for five performance years, ending in 2031.

So What?

ASM represents a major step in CMS’s long-term effort to bring specialists fully into value-based care, this time in the ambulatory setting. Like TEAM, ASM underscores CMS’s shift from voluntary to mandatory models that could leave unprepared providers reeling from financial penalties.

ASM creates a compliance burden for affected specialists, but it’s also an opportunity to earn rewards for the stronger care coordination, data analytics, and clinical infrastructure that health system employed specialists can leverage more effectively than their independent peers.

ASM could also complicate health systems’ ASC strategies at a time when many systems are making substantial financial commitments via M&A. Systems that have built growth strategies around migrating procedures to lower-cost ambulatory settings may face uncertainty if ASM benchmarks or peer-relative scoring mechanisms compress margins and discourage certain case types. Variation in how specialists perform under ASM—especially in randomly selected regions—could create uneven financial results across a system’s ASC portfolio.

Wasteful and Inappropriate Service Reduction (WISeR) Model

What the model does:

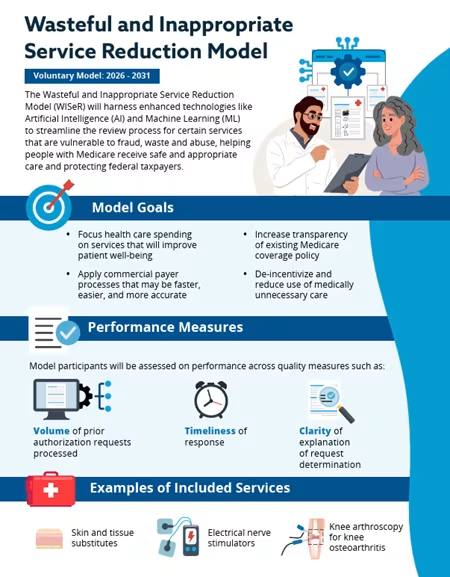

CMS is looking to expand the use of prior authorization in traditional Medicare by leveraging AI, machine learning, and other algorithmic tools to identify potentially unnecessary, low-value, or high-risk services for closer review by human doctors.

Unlike most other models aimed at hospitals and clinicians, the WISeR model participants will be selected technology companies offering their services. The model is functionally mandatory for care providers who deliver the targeted services, as those providers practicing in the model’s demonstration states will not be able to opt out of the prior authorization process.

The demonstration will launch in six states—Arizona, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington—covering select services that CMS has flagged as prone to overuse or fraud, including knee arthroscopy for knee osteoarthritis. Participating technology companies will receive payments based on their ability to reduce unnecessary or non-covered services, raising questions about misincentives and improper care denials.

Implementation timeline:

Announced in June 2025, the model is slated to begin its first performance year in 2026, running for six years. CMS is currently selecting participating technology companies through an open application process.

So What?

The model represents a natural extension of the AI arms race that is unfolding in the RCM space. Payers are aggressively leveraging the technology to tighten utilization management, and providers have started to respond in kind with their own AI tools aimed at pushing back on prior authorization requests and claims coding discrepancies. Now the federal government wants in on the action, but CMS plans to lean on third-party vendors since it lacks the internal expertise to develop these capabilities itself.

Health systems fed up with aggressive prior authorization and utilization management by Medicare Advantage carriers have selectively dropped contracts and turned to traditional Medicare as a safe haven. While limited for now, CMS’s decision to expand prior authorization in traditional Medicare with WISeR could complicate that strategy. Ultimately, systems may find themselves forced to adapt to an era in which AI-driven utilization management becomes the norm across all payer types.

The model’s six demonstration years will be a crucial window for health systems and their advocacy groups to give feedback on where the model falls short. In an ideal world, the model would emphasize transparency and due process, with reasonable utilization guardrails narrowly targeted at low-value procedures. Left unchecked, the model could replicate the same opaque, delay-ridden prior-authorization processes that plague Medicare Advantage.

Achieving Healthcare Efficiency through Accountable Design (AHEAD) Model

What the model does:

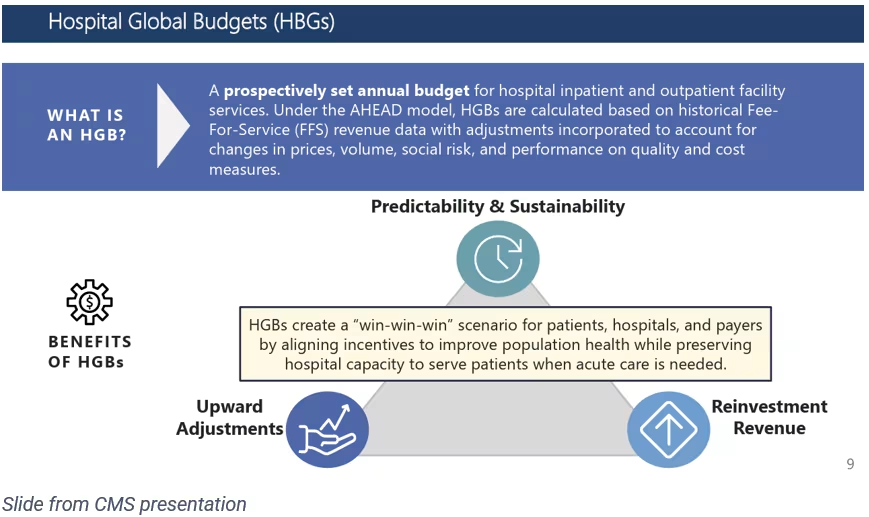

The AHEAD Model is CMS’s next-generation state and regional total cost of care (TCOC) initiative, aimed at helping participating states curb healthcare spending growth while improving population health and care quality.

Building on earlier state-based efforts (like Maryland’s and Vermont’s models), AHEAD gives states, hospitals, and payers a shared accountability structure with global budgets, multi-payer alignment, and population-level quality benchmarks. The model emphasizes prevention, primary care investment, and transparency, requiring states to engage hospitals, primary care organizations, and public health agencies in coordinated planning.

The AHEAD model is voluntary, and participating hospitals will sign agreements with CMS that enumerate requirements and expectations. States can either apply to coordinate across the entire state, or within specific sub-regions. States, hospitals, and primary care practices are all potential participants with their own sets of accountability measures.

Implementation timeline:

Originally announced in 2023, AHEAD underwent significant revisions under the Trump administration in September 2025, extending its performance period and tightening financial accountability requirements.

The revised model will run for ten years through December 2035, with phased onboarding of up to eight participating states. Six states have already been selected: Maryland, Vermont, Connecticut, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and select New York counties (including the Bronx, Kings, Queens, Richmond, and Westchester County).

Early implementation states are expected to begin performance periods in 2026, with additional states joining in 2027 and beyond.

So What?

AHEAD represents CMS’s most ambitious effort to move entire state systems toward population-based payment and integrated health planning (features more commonly associated with single-payer healthcare systems like Canada and the UK). For health systems, the model elevates the importance of cross-sector collaboration—linking hospitals, primary care, and public health under unified cost and quality goals.

While the expanded reporting and budgeting requirements create a heavy compliance lift, AHEAD also gives hospitals a chance to stabilize revenue through predictable budgets and influence over how total-cost targets are set.

In a broader sense, the model underscores CMS’s commitment to testing statewide accountability frameworks that could eventually reshape how Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial payers operate in tandem. While this model is voluntary for now, it could become a blueprint for future mandatory models.

Other innovation models worth mentioning

In addition to the four models above, it’s worth quickly recapping a handful of other models that the Trump administration is also moving forward with or reshaping:

The Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Model: The administration is moving forward with this mandatory model for kidney transplant hospitals that ties payments to transplant rates, organ offer acceptance, and post-transplant outcomes.

The Cell and Gene Therapy Access (CGT) Model: The administration is expanding participation in this voluntary outcomes-based model, which allows states to make performance-linked payments for costly gene therapies like those treating sickle cell disease. Officials have positioned CGT as a way to control drug spending while preserving access to breakthrough treatments.

The Integrated Care for Kids (InCK) Model: CMS is scaling down and modifying this existing pediatric care coordination model. The agency has signaled plans to reduce award sizes and tighten evaluation criteria, arguing that earlier iterations lacked clear cost-saving potential.

Our final thoughts

Taken together, CMS’s emerging portfolio of innovation models points to a future where no corner of care delivery is exempt from value-based risk. Health systems that succeed will be those that anticipate CMS’s direction—investing early in care coordination, cost analytics, and physician engagement—rather than waiting to react when participation becomes mandatory.

Ironically, this shift comes at a time when many health system leaders are increasingly disillusioned with commercial VBC arrangements as a revenue diversification strategy (a sentiment we heard at the Academy’s CSO Forum last Spring). That tension underscores the challenge ahead: even as confidence in commercial value-based contracts wanes for some CSOs, CMS is doubling down on risk as an organizing principle of federal payment policy.

It’s ultimately a sink-or-swim moment for health systems as they face a proliferating number of mandatory payment models with substantial downside risk in segments that were previously reliable margin generators.