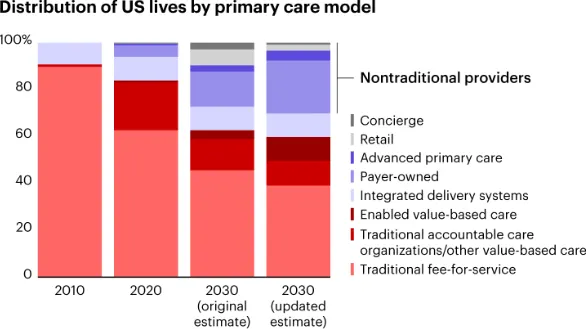

Over two years ago in August 2022, Bain came up with a surprising prediction: that “nontraditional” players could capture up to 30% of the primary care market by 2030. The prediction reflected the headlines at the time—these players seemed to be gaining traction and many had spent tens of billions on primary care acquisitions (e.g., CVS-Oak Street, Walgreens-VillageMD, Optum’s buying spree).

Specifically, Bain predicted that:

Retail behemoths would capture 5-10% of volumes by 2030

Payers would capture up to 15% of the market (up from 5% at the time)

Virtual visits could total 20% of volumes by 2030 (up from 12%)

Now, two years later, the headlines look different. Walmart shuttered its fifth attempt at healthcare while Walgreens looks to divest its share in VillageMD. CVS is facing sizable headwinds, while Optum has been quietly divesting or closing many primary and urgent care locations. Some analyses show that “new entrants” (not including payers) are capturing just over 1% of commercial volumes for low-acuity care in target markets. And yet, Bain just released an updated report and kept the same prediction. Do we believe them?

The state of “disruptors” in primary care today

In its updated prediction, Bain keeps its overarching idea that a third of the market will be captured by non-traditional providers—however, it updates the victors in the new estimate. In general, we see three shifts:

1. Retailers now hold a far smaller share of the prediction.

Bain shares recent survey data finding that less than a third of consumers are likely to seek a health screening at a retailer, even though 71% would go to one for a vaccination. They suggest that retailers will have to strengthen their healthcare expertise and invest in marketing to lead consumers to associate their brand with high-quality care.

Our reaction: We think it’s right to be skeptical of this ability. Retailers have already attracted substantial healthcare talent (including many leaders from health systems) and have invested billions in marketing to change consumer sentiment about their quality. And while much of that was working—certain retailers were attracting more patients for more complex care—shareholders pressures have hamstrung these efforts. So have real estate challenges which often force co-location of clinics.

2. Payers hold a slightly larger share—making up for the retail gap.

Bain now predicts that payers will account for 20% of the market by 2030.

Our reaction: This makes sense, despite some pullback from players like Optum, since Humana and Elevance have been moving full steam ahead into the market with the backing of major PEs. However, we expect many of these efforts to now be focused more on the senior population rather than commercial.

We think much of Bain’s prediction will hinge on the DOJ investigation into Optum and their vertical integration as well as if the Trump administration takes up the mantle. If they do, payers may avoid additional primary care acquisitions that could take years to go through approvals. The outgoing Biden administration just released a proposed rule asking for more information about payer vertical integration in MA and how it impacts competition—we’ll have to watch if CMS under new leadership uses these comments.

3. Advanced primary care (APC) players also have a slightly larger share of the new prediction as do value-based care enablers.

Bain believes that independent primary care practices won’t be able to get fee-for-service contracts from payers much longer. Therefore, they contend that APC players and value-based enablers like agilon, Aledade, and Privia will get more business and more financial backing.

Our reaction: These players have grown substantially in the past two years but face strong headwinds now in Medicare Advantage with new coding models (V28) that are impacting the bottom line. Bain asserts that true winners will be those that can actually deliver on lower cost of care (while maintaining high quality), which we think is true of course. But we also believe that scale and the ability to shift patients to other models (like ACO REACH or MSSP) will be vital for those players to be able to withstand headwinds.

Where does this leave health systems?

According to Bain, health systems, “under pressure from population-focused disruptors and nontraditional providers, face a challenging road ahead.” This stands in divergence from many health system executives we’ve talked to recently who generally aren’t as concerned with disruptors as they were even a year ago.

Ultimately, we don’t think looking at market share capture is the best way to understand the threat. While Bain undoubtedly might inflate its numbers a bit to make a splash in headlines, a lot could change in the next five years. And we agree with the overarching point that primary care “disruptors” (whatever form they are in) will continue to figure out the market and the right strategy to grab more share (especially those like payers with a vested interest).

Rather, we believe that the greater threat from primary care disruption presents is the shift in how consumers and patients perceive care and access to care. We think the health systems that thrive under this new market will be those that carefully segment their population and offer different access channels to different types of primary care patients: e.g., those that want care within the day, those that want a long-term PCP relationship, those that want a wraparound model (often seniors) and those that want mostly digital, asynchronous care. We believe such systems will be best able to survive in whatever market truly exists in 2030.